known as dermatology and syphilology.

Endemic,

old-world

diseases like leishmani-

asis and garlic burns from folkloric medicine

echoed this sentiment of a traditional medi-

cal setting of a bygone era. By no means was

there a lack of technology; YAG and CO2

lasers, as well as a hair-transplant system akin

to the NeoGraft, were readily available.

A bit of pharmacotherapy culture

shock occurred as I became used to hearing

names like fusidic acid—an antibiotic used

extensively throughout the world but only

approved in 2011 in the United States after

I came back from the first trip—and various

regional preparations of betamethasone and

petroleum jelly.

Patient interaction was another platform

for learning. Every patient that walked in

was greeted with the word

salamtek

, a phrase

basically meaning “I hope you feel better.”

Jordan is considered a conservative country,

so the impression a phrase like that evokes is

only a fraction of how typical social dynam-

ics occur. Patients would often walk in wear-

ing a face veil (niqab), which I would assume

meant they must be from a very conservative

area; but in reality, they were hiding very

debilitating skin lesions.

It was a reminder that every patient

needs a clean slate in judgment despite

previous cases. A lighter tone definitely

existed, especially when elderly men figuring

that since sexually transmitted diseases were

treated here, erectile dysfunction must be

as well. After being congratulated on the

longevity of their virility, these gentlemen

5

COM Outlook . Fall 2013

s a fourth-year medical student in

2011, I had the opportunity to do

a rural selective dermatology rota-

tion in King Hussein Medical Center in Am-

man, Jordan. I knew it was going to be a great

experience when, on my first day, I walked

in on a lecture about a patient currently on

the service being treated for toxic epidermal

necrolysis. From then, it seemed a constant

kaleidoscope of skin nosology ranging from

textbook-only genodermatoses to diseases

common in the United States—but on a dif-

ferent side of the spectrum of severity.

Rather than simple mild-plaque psoria-

sis, a patient with erythroderma psoriasis

would come in, or rather than simple acne

vulgaris, a case of Morbihan disease would

present. Shingles in the United States is

the same as shingles anywhere else, but the

backdrop of a third-world country has the

effect of mystifying a disease.

Because I enjoyed my first experience

so much, I jumped at the opportunity to

visit the region again in my second year of

residency. With the nonbullous ichthyiosis

erythroderma and Netherton syndrome

cases still etched in my mind, I anticipated

what diseases I would encounter on this trip.

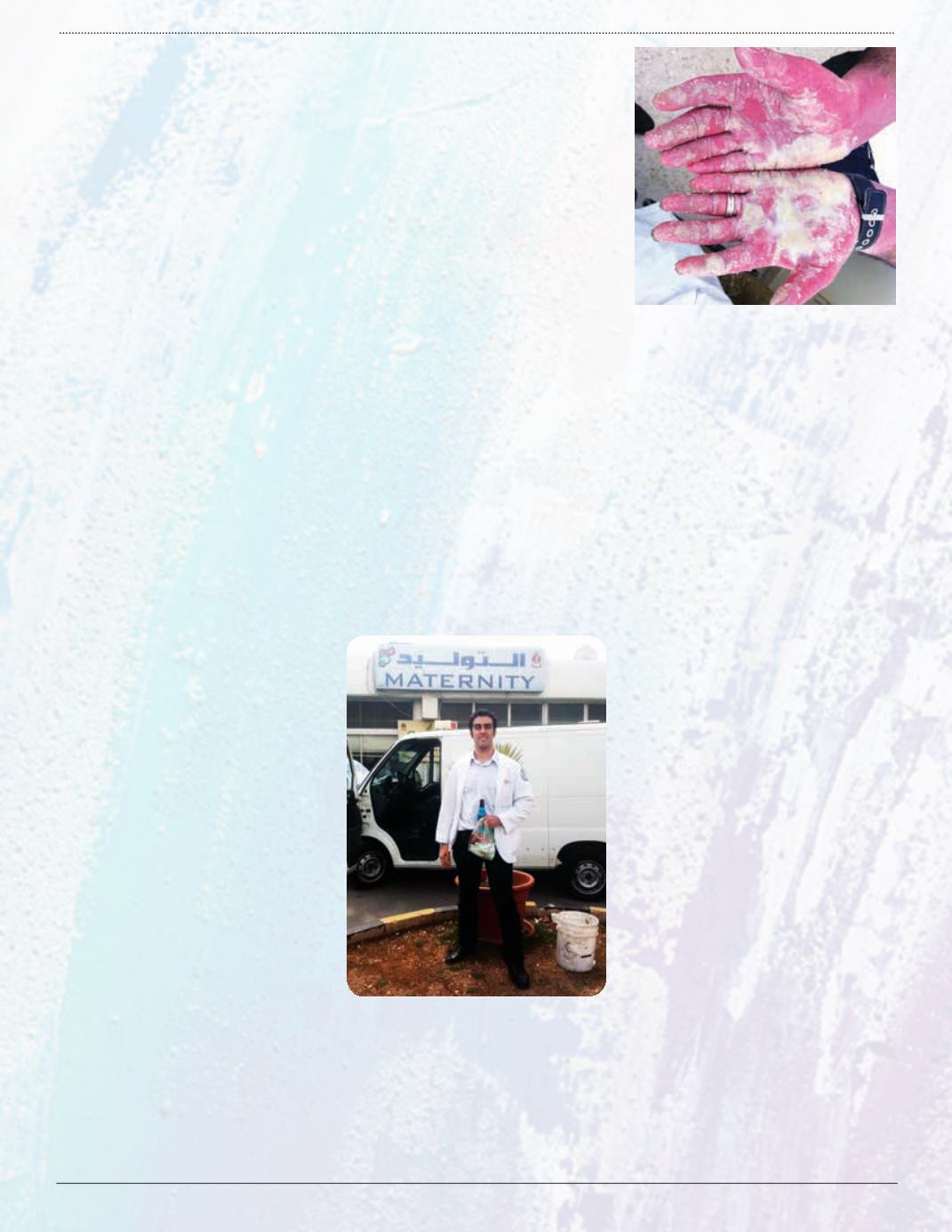

I was academically pleased with the chronic

myiasis, Vohwinkel syndrome

(pictured above

right)

, and pityriasis rotunda that could now

be added to the diseases experienced in my

career. A good case of paraneoplastic pem-

phigous or fungating psoriasis does much to

overturn old trainee complaints that derma-

tology rotations are only cosmetic or have

boring pathology. In fact, there are quite a

few dermatology-related emergencies.

In Jordan, the specialty is still known as

dermatology and venereology, much like it

was in the United States, where it was once

A

Dermatology

Rotation

Offers

Eye-Opening

Insights

By Omar Mubaidin

2011 NSU-COM Alumnus

would be politely directed to a department

that handled their complaints.

Because there was a formal Anglophone

mandate, medical education in Jordan was

taught entirely in English, so my own dif-

ficulty with Arabic was not a problem there.

Another interesting fact was how some sce-

narios of the medical education experience

do not change. Listening to the interactions

between residents and their attending was

very similar to sitting in resident lounges in

any of the South Florida teaching hospitals.

The influx of Syrian refugees provided a

new element to my residency experience. The

Zaatari refugee camp is now the second-larg-

est refugee camp in the world. With 144,000

people, this camp is now Jordan’s fourth-

largest city. I had the opportunity to go to a

primary care clinic for two days where most

of the diseases treated were rashes, upper-

respiratory infections, and diarrhea that were

more a function of living conditions associ-

ated with mass displacement.

Despite being a refugee camp, a self-

contained economy was thriving because

people had been living there for over a

year. The

main street,

which also included

field hospitals from various countries, had

butcher shops, a barber shop, a restaurant,

and a hookah lounge. Unfortunately, to go

along with the trappings of a brutal civil war,

there were stories of infiltrators trying to

poison the water system, prostitution, abuse,

and AIDS cases—an entity infrequently

encountered in that part of the world.

This was my first experience in a refugee

camp, which was more than memorable. In

fact, the entire trip of contrasts and similari-

ties in health care delivery taught me many

lessons I will hopefully carry forward for the

rest of my career.